The Curonians were a Baltic tribe that used to live on a narrow strip of the Baltic coastline from the 1st to the 14th centuries in what is now Lithuania and Latvia. Historians say that the Curonians were a wealthy and powerful tribe who sailed the sea unrestricted and shared influence over the sea with the residents of the Western coast of the Baltic Sea.

They battled Danes and Swedes

Polish historian Jerzy Litwin, whose article is included in the Lithuanian Sea Museum's book “Vėjas rėjose. Burlaivių epochos atspindžiai Lietuvoje”, notes that Curonians were once considered to be the “most brutal tribe” among the Balts.

They received this nickname from the German chronicler Adam of Bremen. However, it is believed that Curonians were forced to be brutal by their surroundings: from the 8th to the 9th century, the lands of the Baltic coast became the target of Scandinavian war raids.

In 853, the Curonians were attacked by the Danes. As Bremen-Hamburg archbishop Rimbert wrote in his biography of St. Ansgar, “the Danes collected a multitude of ships and travelled to the Curonian lands, which they wanted to raid and enslave. This land had five states. When the people learned of their coming, they collected themselves into one place and took up a manly defence. In their battle, they destroyed the Danes, pillaging their ships and taking their gold, silver and other treasures.”

However, in 854, Swedish king Olof attacked with a large navy and 7,000 warriors. The Swedes razed the Curonian city of Seeburg and raided Apuolė. The Curonians defended their Curonian capital (which is now a village in the Skuodas region) for eight days, but on the ninth day of the siege, they began negotiations with the Swedes, ransoming themselves for silver and exchanging 30 hostages in return for their loyalty.

Now, since 2004, the annual Apuolė 854 ancient Baltic tribal warfare and craft festival is held on the Apuolė castle mound on the second-to-last weekend of August.

After recovering from the assaults, the Curonians and Prussians were sure to return the favour, pirating Scandinavian ships and organising raids on the Scandinavian coast.

In the 11th century, the Danes tried to raid the coasts inhabited by the Balts. In the 12th century, the Teutonic order followed the Danes' example and, under the cover of a Christian mission, moved into the region. They colonised Livonia and founded the city of Riga. In the 13th century, the Danes conquered Estonian lands. Therefore, the appearance of sails on the horizon were always a cause for distress for coastal people, who often expected them to be to a sign of approaching enemies.

In a history of the archdiocese of Cremen and Hamburg written by Adam of Bremen in the 11th century, there are many mentions of the Curonians. He wrote that it was eight days' journey to Courland, that the Curonians were a brutal tribe, and that all fled from the heathens. He also mentioned that Courland had much gold and many excellent horses, and that their homes were full of wise men, prophets and soothsayers. These were sought by people from all over the world looking for answers, but mostly by Greeks and Spaniards.

More active than the Prussians

Military historian Dr. Manvydas Vitkūnas says that the Curonians were much like Vikings and that, when it came to naval warfare, they may have been more active than the other coastal Baltic tribe – the Prussians.

“In the middle of the 8th century, the Curonians were said to have fought in the battle of Bravalla between the Swedes and Danes. From 830 until 930, no fewer than ten Scandinavian (Swedish and Danish) incursions into Curonian lands are mentioned. However, from the second quarter of the 9th century to the middle of the 11th century, the Curonians were rarely attacked, and from the middle of the 11th century, the Curonians take over the Scandinavian role in the Baltic Sea and become more active than the Swedes and Danes,” Vitkūnas said. “The Curonian naval raids only end in the 13th century, when many of the coastal lands have been taken by the Germans.”

Raiders or merchants?

Curonian seafarers, like the Scandinavians, found a balance between warfare and commerce, said Vitkūnas. They attacked not only ships on the open seas, but the coasts of neighbouring countries as well.

“In the 12th century, the Curonians raided the islands of Blekinge (southern Sweden) and Møn (eastern Denmark). In around 1170, Danish king Valdemar the Great, in an effort to guarantee peace during the year of his son's coronation celebrations, sent ships to rid the Baltic sea of pirates in a larger than usual radius around Denmark,” said Vitkūnas.

“This example shows that the Curonian naval raids had reached a truly significant scale, if a naval kingdom as strong as Denmark had to hold a serious offensive operation to protect itself from the danger presented by the Curonians.”

Lithuanian Sea Museum historian Dainius Elertas, in the previously mentioned book by the same museum, also said that the Curonians always competed with the Scandinavian Vikings: “Curonian warships often worked together with Estonians and western Slavs. Sometimes, they also got involved in Scandinavian Vikings' war raids. In those times, commerce, raids and piracy were activities that complemented one another.”

Attempts to conquer Riga

Livonian chronicler Henry of Latvia's description of Riga bishop Albert's encounter with the Curonians in 1210 makes it clear that the Curonians had their own naval warfare strategy:

“When the bishop and their pilgrims departed for Gotland and left Livonia with all of his men and some pilgrims, the Curonians, enemies of the name of Christ, suddenly appeared at the strait on the coast with eight pirate ships. The pilgrims who saw them got out of their cogs into boats to defend themselves from the pagans, but in their carelessness, each boat rushed forward to meet the enemies. The Curonioans unloaded their pirate ships' noses and faced the approaching boats, setting their ships in pairs and leaving gaps between the pairs.

"When the pilgrims approached with their first ships, they found themselves surrounded by pirates, and because their boats were small, the pilgrims couldn't reach their enemies, who were riding much higher than they were. The Curonians killed some pilgrims with spears, others drowned, some were wounded, and the remainder were forced to return to their cogs and retreat.

"Then, the Curonians gathered the dead, undressed them, distributed their clothes, and took everything else they found among the dead. After that, the city people of Gotland gathered the dead and buried them honourably. There were 30 knights and others. The bishop announced several days of mourning...”

Elertas, who has researched Curonian strategy, emphasised that when the Curonians tried to take Riga in June 1210, chronicler Henry of Latvia wrote that they had so many boats that the “entire seas seemed covered in a thick cloud.” A few years later, however, the Frisians (a famous seafaring people who lived by the North Sea) had revenge on the Curonians by surrounding them by the island of Gotland and killing almost all of them.

Swallowed up by the Order

“In the 13th century, chronicler Henry of Latvia wrote that the Curonians had long been accustomed to raiding Swedish and Danish lands to take slaves, sheep and other wealth, as well as Christian church bells, which they would melt down to make weapons and jewellery,” said Vitkūnas.

“In the beginning of the 13th century, as the Teutonic Order began establishing itself on the Baltic coast, the Curonians continued operating in the sea for some time and even fought German naval forces more than once. Unfortunately, they quickly (perhaps due to internal fractures and inability to focus their forces on resistance) were seized by the Order (except for that portion of Curonian lands that became part of the Lithuanian state).”

The Curonians' regular campaigns in the sea and their seamanship, according to Vitkūnas, created the preconditions for further development of Baltic seamanship, but their territorial losses and the excessively small stretch of the Baltic coast held for a long period by the Lithuanian state never gave them the opportunity to take advantage of this.

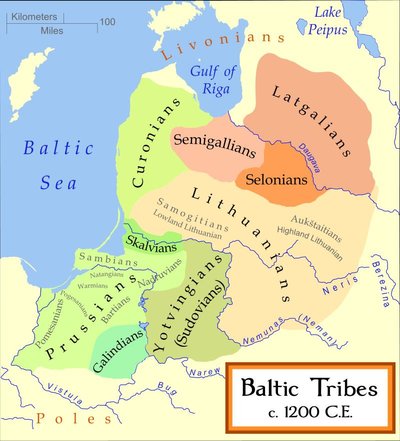

The Curonians, who failed to build a state, were forced to recognise the rule of the Brothers of the Sword and the Livonian order in the 13th century. They rose up after the Lithuanians' victory in the battle of Saulė in 1236 and after the battle of Durbė in 1260, but they were suppressed by the Order. Part of the Curonians moved to Lithuania: southern Curonians assimilated with the Samogitians while the northern Curonians became Latvian by assimilating with the Semigallians and the Livonians.