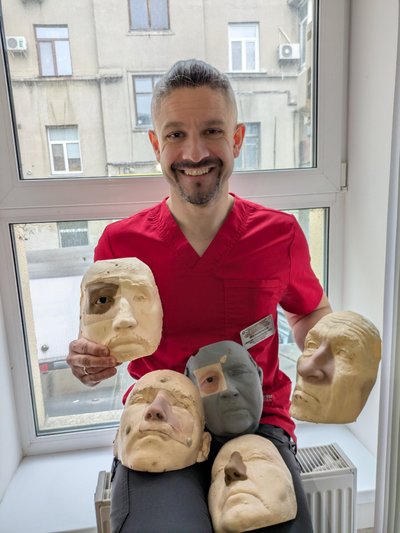

Traditional plastic surgery often cannot repair extensive injuries, requiring innovative solutions. The work involves creating prosthetics for eyes, ears, and noses using advanced technologies such as facial scanning and 3D printing. The prosthetics are crafted in collaboration with Ukrainian sculptors. The final products are attached using adhesives or special magnets and must be aesthetically fitting and comfortable to wear.

Prosthetics Are Expensive

Creating prosthetics is a complex and costly process. The cost of a single prosthetic can reach up to €2,500. However, Filonenko provides prosthetics free of charge to soldiers and civilians affected by the war, relying on volunteer assistance and donations. He openly admits to contributing his own money to support others, describing it as his mission.

Although his work brings relief to patients, it is emotionally taxing, as every trauma is accompanied by a tragic story.

Filonenko’s interest in facial prosthetics began before the war when he started helping cancer patients whose faces were severely affected by surgeries.

"Initially, I worked for a long time as a dentist in the private sector, treating teeth and achieving good results. Yes, I earned money, but I couldn’t accept working solely for money. It’s against my nature. I started collaborating with a friend who is a qualified surgeon. We worked together for 15 years and performed many surgeries. He’s now a professor of maxillofacial surgery," Filonenko shares.

Since facial prosthetics was a little-developed field in Ukraine, with no specialists, he had to seek learning opportunities on his own. He connected with Western colleagues via social media and began collaborating with them. Their shared knowledge, advice, and experience enabled him to start creating facial prosthetics.

"This Is Not Normal"

"In Ukraine, this was considered part of dentistry, and this field did not exist as a separate specialty. Some people worked on it sporadically, but no one systematically addressed it. For me, it was a personal challenge—not because I didn’t want to understand, but because I couldn’t accept how a doctor or official could tell someone: ’You have no nose; just live without it!’ There are cases where surgery isn’t an option for various reasons. When a person has a defect in their face—whether it’s a missing nose, eye, or ear—it drastically reduces their quality of life. Instead of finding solutions, they’re told to live with it, hide away, or even give up on life. That’s not normal," Filonenko says.

Creating facial prosthetics begins with scanning the patient’s face to produce a digital 3D model. This serves as the foundation for further work and allows the creation of a prosthetic that fits the patient’s facial contours. Based on this model, an initial prototype is made, which is refined by a sculptor. The sculptor uses special materials to create an accurate shape and details that match the lost facial feature’s original appearance. The prototype is then replaced with silicone, which is flexible, comfortable, and suitable for the final prosthetic.

Pain Cannot Wait for Bureaucracy

How does Filonenko sustain himself while offering his services for free?

"I don’t know. If I thought about it too much, I probably wouldn’t have started. Someone helps here, I come up with something there, and I earn some money myself—for instance, by teaching courses on prosthetics using dental implants. If you look at the official records, everything is supposedly fine in our healthcare system. But in real life, I have a soldier in my ward who can’t receive painkillers because we’ve run out, and they’re waiting for procurement to be organized. Meanwhile, he’s in great pain. That’s our reality," he explains, adding that anyone who speaks out loudly about such issues risks being dismissed.

Filonenko notes that it’s common for the state to provide an inappropriate prosthetic, like giving a person who lost their right eye a prosthetic designed for the left, and consider it "good enough."

"The state is actually the least helpful. We’re grateful that our lab belongs to a private company. We’re thankful they simply don’t interfere. We’re not asking your government or, for example, Estonia’s government for money. But if someone wants to help us, they can," he says, emphasizing that he provides receipts for every hryvnia, euro, or dollar spent to ensure transparency.

Coping With Emotional Burden

How does Filonenko emotionally cope with what he sees and hears?

"My friend, a professor, often says there are three ways to deal with it: suicide, alcohol, or love. That’s why I love my wife very much—she’s my support," he remarks.

Filonenko explains that he follows the principle of not bringing work experiences home.

"Lately, I’ve been asking people not to share excessive details about their stories with me. While it might help them to express their feelings, that’s what psychologists are for—it’s their job," he says.

At the same time, he admits to having heard and seen horrifying things.

"One young man spent a long time on the front line and was severely injured there. Afterward, he was cared for in a hospital by a young nurse. They became close and decided to inform their parents about their plans to marry. While walking around a city near the front, the Russians were dropping grenades from drones to train their drone operators. One grenade landed between the young man and the nurse. He grabbed the grenade to throw it away, but it exploded, costing him his hand and both eyes. He was just 23. But the girl survived because of him," Filonenko recalls, admitting that such stories make it hard to focus on his work.

The Most Rewarding Moments

What are the most rewarding aspects of his work? Filonenko is more eager to talk about this.

"The best part is when someone gets back a piece of normal life. One story involved a man who came home, and his child was so scared by his missing eye that they ran to another room. We made an eye prosthetic for him. I don’t know the details, but after that, he could interact normally with his child. That was incredibly moving," he shares.

The most heartfelt moments, he adds, are always when someone tries on their new prosthetic for the first time.

"When a person looks in the mirror and says, ’Oh, I have hope!’ That hope is the most important thing."

Empathy in Wartime

Amputees are a common sight in Ukrainian streets. Has this changed attitudes toward people with disabilities?

"From my personal experience, people don’t point fingers, laugh, or humiliate them anymore. Instead, they often look away because they feel awkward. But this hurts the injured even more—they feel like people don’t even want to look at them," Filonenko explains.

He recalls speaking with a person who had lost a leg, who said they felt worthless, as if they didn’t even deserve others’ attention.

"I can’t imagine how someone feels losing their sight in an instant, like a light being switched off. Even thinking about it is terrifying. I can somewhat imagine how someone gradually loses their sight over time. But to lose it instantly—that’s too much," he says.

Does war foster empathy in ordinary people?

"I believe it does. Many have told me that the war has profoundly changed their attitudes toward life and values. But it hasn’t changed me. My values have always remained the same. I’ve never had ridiculous desires, like wanting an expensive car. Why? My values have stayed completely intact, even strengthened. I’m now more confident that they’re the right ones. I used to consider myself a bit odd, but now I understand that if others think differently, that’s their issue, not mine. I wish more people thought this way. But people are different, and they must be respected, no matter who they are," the doctor concludes.